Joshua M. Pearce, Michigan Technological University

As COVID-19 wreaks havoc on global supply chains, a trend of moving manufacturing closer to customers could go so far as to put miniature manufacturing plants in people’s living rooms.

Most products in Americans’ homes are labeled “Made in China,” but even those bearing the words “Made in USA” frequently have parts from China that are now often delayed. The coronavirus pandemic closed so many factories in China that NASA could observe the resultant drop in pollution from space, and some products are becoming harder to find.

But at the same time, there are open-source, freely available digital designs for making millions of items with 3D printers, and their numbers are growing exponentially, as is an interest in open hardware design in academia. Some designs are already being shared for open-source medical hardware to help during the pandemic, like face shields, masks and ventilators. The free digital product designs go far beyond pandemic hardware.

The cost of 3D printers has dropped low enough to be accessible to most Americans. People can download, customize and print a remarkable range of products at home, and they often end up costing less than it takes to purchase them.

From rapid prototyping to home factory

Not so long ago, the prevailing thinking in industry was that the lowest-cost manufacturing was large, mass manufacturing in low-labor-cost countries like China. At the time, in the early 2000s, only Fortune 500 companies and major research universities had access to 3D printers. The machines were massive, expensive tools used to rapidly prototype parts and products.

More than a decade ago, the patents expired on the first type of 3D printing, and a professor in Britain had the intriguing idea of making a 3D printer that could print itself. He started the RepRap project – short for self-replicating rapid prototyper – and released the designs with open-source licenses on the web. The designs spread like wildfire and were quickly hacked and improved upon by thousands of engineers and hobbyists all over the world.

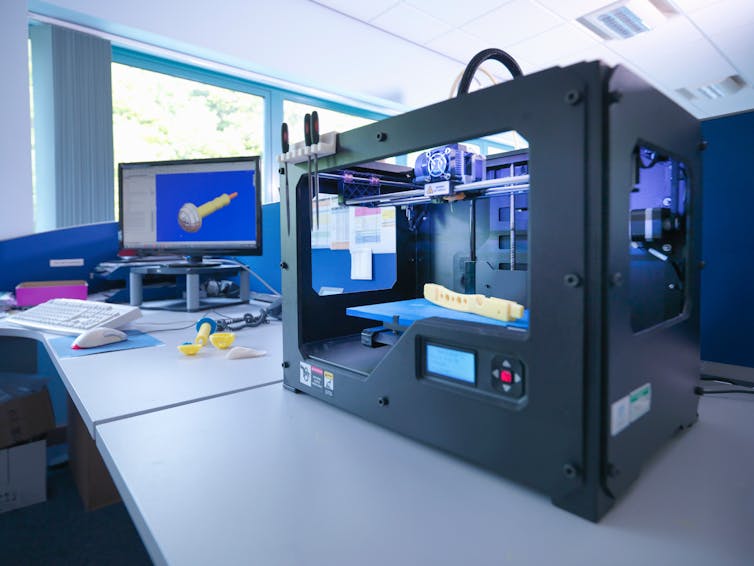

Many of these makers started their own companies to produce variants of these 3D printers, and people can now buy a 3D printer for US$250 to $550. Today’s 3D printers are full-fledged additive manufacturing robots, which build products one layer at a time. Additive manufacturing is infiltrating many industries.

My colleagues and I have observed clear trends as the technology threatens major disruption to global value chains. In general, companies are moving from using 3D printing for prototyping to adopting it to make products they need internally. They’re also using 3D printing to move manufacturing closer to their customers, which reduces the need for inventory and shipping. Some customers have bought 3D printers and are making the products for themselves.

This is not a small trend. Amazon now lists 3D printing filament, the raw material for 3D printers, under “Amazon Basics” along with batteries and towels. In general, people will save 90% to 99% off the commercial price of a product when they print it at home.

Coronavirus accelerates a trend

We had expected that adoption of 3D printing and the move toward distributed manufacturing would be a slow process as more and more products were printed by more and more people. But that was before there was a real risk of products becoming unavailable as the coronavirus spread.

A good example of sharp demand for 3D printed products is personal protective equipment (PPE). The National Institutes of Health 3D Print Exchange, a relativity small design repository, has exploded with new PPE designs.

Already, because of the global impact of the coronavirus, 94% of Fortune 1000 companies are having their supplies chains disrupted and businesses dependent on global sourcing are facing hard choices.

The value of industrial commodities continues to slide because the coronavirus has put a major dent in demand as manufacturers shut down and potential customers are quarantined. This will limit people’s access to products while increasing their costs.

The disruptions to global supply chains caused by strict quarantines, stay-at-home orders and other social distancing measures in industrialized nations around the world present an opportunity for distributed manufacturing to fill unmet needs. Many people are likely, in the short to medium term, to find some products unavailable or overly expensive.

In many cases, they will be able to make the products they need themselves (if they have access to a printer). Our research on the global value chains found that 3D printing with plastics in particular are well advanced so any product with a considerable number of polymer components, even if the parts are flexible, can be 3D printed.

Beyond plastics

Making functional toys and household products at home is easy even for beginners. So are adaptive aids for arthritis patients and other medical products and sporting goods like skateboards.

Metal and ceramic 3D printing is already available and expanding rapidly for a range of items, from high-cost medical implants to rocket engines to improving simple bulk manufactured products with 3D printed brackets at low costs. Printable electronics, pharmaceuticals and larger items like furniture are starting to become available or will be in the near future. These more advanced 3D printers could help accelerate the trend toward distributed manufacturing, even if they don’t end up in people’s homes.

There are some hurdles, particularly for consumer 3D printing. 3D printing filament is itself subject to disruptions in global supply chains, although recyclebot technology allows people to create filament from waste plastic. Some metal 3D printers are still expensive and the fine metal powder many of them use as raw material is potentially hazardous if inhaled, but there are now $1,200 metal printers that use more accessible welding wire. These new printers as well as those that can do multiple materials still need development, and there’s a long way to go before all products and their components can be 3D printed at home. Think computer chips.

When my colleagues and I initially analyzed when products would be available for distributed manufacturing, we focused only on economics. If the coronavirus continues to disrupt supply chains and hamper international trade, however, the demand for unavailable or costly products could speed up the transition to distributed manufacturing of all products.

Joshua M. Pearce, Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, and Electrical and Computer Engineering, Michigan Technological University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.