ManMohan S Sodhi, City, University of London and Christopher S. Tang, University of California, Los Angeles

Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan has elicited a strong response from China: three days of simulated attack on Taiwan with further drills announced, plus a withdrawal from critical ongoing conversations with the US on climate change and the military.

This strong reaction was predictable. President Xi had earlier warned President Biden not “to play with fire”. Of course, if Pelosi’s visit hadn’t gone ahead, the Biden administration would have faced a strong reaction from both parties in Congress for not standing up to China’s threat to Taiwan or human rights issues regarding Tibet and Xinjiang, not to mention Hong Kong.

So where does it leave trade between the world’s two leading powers?

How business trumped ideology

Consider the not-too-distant past. The US supported the Republic of China against Japan in the Pacific war of 1941-45. When the Chinese leadership fled to Taiwan in 1949 following the victory of Mao Zedong’s communists in the Chinese civil war, Washington continued to recognise the exiled regime as China’s legitimate government, blocking the People’s Republic of China (PRC) from joining the United Nations.

This shifted in 1972 following President Nixon’s historic visit to China (in a move to isolate the Soviets). The US now recognised the PRC as China’s sole government and accepted its One China policy. It downgraded its Taiwan relations to merely informal, while affirming a peaceful settlement to the mainland communists’ claim that this was a breakaway province that had to be assimilated.

This opened US-China trade, ending a US trade embargo in place since the 1940s. Economic ties proliferated in the 1980s under Mao’s eventual successor, Deng Xiaoping, helping the Chinese economy to multiply while the US enjoyed lower consumer prices and a stronger stock market.

Western manufacturing firms either outsourced to Chinese firms or set up operations themselves. They benefited from cheaper production and – for those outsourcing – not having to own factories or deal with labour issues. In turn, the Chinese gained tremendous manufacturing capability.

As China’s middle class grew wealthier, the country became a major target consumer market for US firms such as Apple and GM. The Chinese authorities insisted this was done through local partner firms, transferring technology in the process and further enhancing the nation’s manufacturing know-how.

The growing Chinese threat

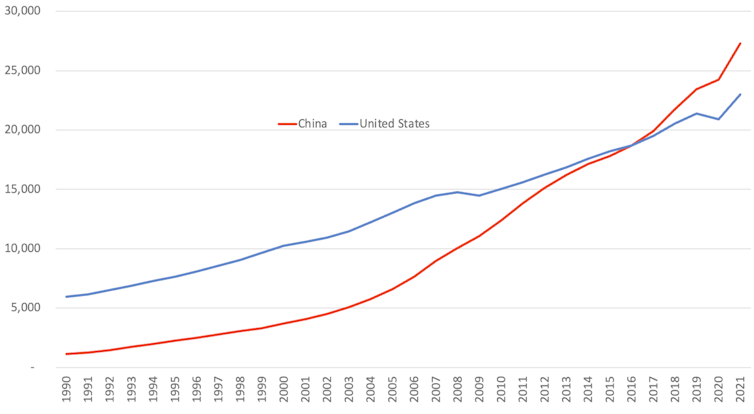

China and the US captured more than half the growth in GDP across the world from 1980 to 2020. US GDP grew nearly five times from US$4.4 trillion (£3.6 trillion) to US$20.9 trillion (£17.3 trillion) in today’s money, while China’s grew from US$310 billion to US$14.7 trillion.

China is now the second largest economy, although the IMF, World Bank and CIA consider it the largest once purchasing power is taken into account (see chart below). The US is still well ahead on per capita income (US$69,231 vs US$12,359 in 2021), though China’s is now that of a “developed” country, having lifted 800 million people out of poverty in the process.

The US has become increasingly concerned about China’s faster economic growth and the fact that the US buys much more from its rival than the other way around. This drove the big decline in US domestic manufacturing that famously helped Donald Trump to win the US presidency.

Chinese and US GDP based on purchasing power parity 1990-2021

Equally, the rivalry has extended to other areas as China has sought a leading role on the world stage. Both nations are nuclear powers, although the Chinese military has only 350 nuclear warheads to America’s 5,500.

China has a larger navy, with some 360 battle force ships compared to the US 297, although China’s are mostly smaller – only three aircraft carriers compared to America’s 11, for example. The two countries are also competing in space to bring astronauts to the Moon and establish the first lunar base.

All this has threatened American dominance, while President Xi has also been much more forthright both domestically and internationally than any Chinese leader since Mao. The US has gradually become more hostile, starting with President Obama’s pivot towards other Asian nations in 2016 and then President Trump’s public complaints and eventual sanctioning of China’s “unfair” trade practices.

Trump imposed extra tariffs on goods imported from China in 2018 and restricted China’s access to various semiconductor manufacturing technologies in 2020, while the Chinese responded with countermeasures along the way.

When President Biden took office in 2021, he began highlighting long-simmering complaints about human rights issues in Xinjiang and the threat to Taiwan (while still endorsing the One China Policy). He also imposed sanctions on certain Chinese companies of a kind not been seen since the Mao-era trade embargo.

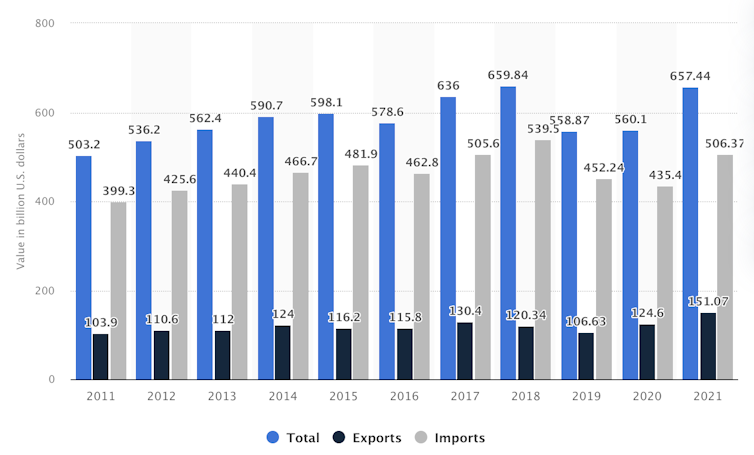

US trade in goods to China 2011-21

Biden also banned goods from China’s Xinjiang region on the grounds of forced labour in 2022, affecting the purchasing of goods by many western companies. China reportedly moved workers to other parts of the country to enable western companies to keep purchasing.

Bipolarity is back

COVID-19 further increased the distance between the two countries. After China’s zero COVID policy helped to disrupt supply chains and cause product shortages, the Biden administration began calling for reduced dependency on its rival.

US firms have duly been restructuring their supply chains. In June, Apple moved some iPad production from China to Vietnam, albeit also because of growing demand in south-east Asia.

Near-shoring to Mexico is gaining momentum. Apple manufacturers Foxconn and Pegatron are considering producing iPhones for North America in Mexico rather than China to take advantage of lower labour costs and the free-trade agreement between the US and Mexico.

Two global blocs are increasingly emerging, with US treasury secretary Janet Yellen in April calling for “friend-shoring” with trusted partners, dividing countries into friends or foes. The Biden administration announced at the June G7 meeting a new “Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment”. Aiming to mobilise US$600 billion in investments over five years, this is an overture to various developing countries already being courted by China under its similar Belt and Road Initiative.

Days earlier, China had hosted the annual BRICS summit, which includes Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa. It welcomed leaders from 13 other countries: Algeria, Argentina, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Kazakhstan, Senegal, Uzbekistan, Cambodia, Ethiopia, Fiji, Malaysia and Thailand. Xi urged the summit to build a “global community of security” based on multilateral cooperation. Iran and Argentina have since applied to join the bloc.

We are already seeing what bipolarity will mean for vital components and commodities. In nanochips, the US is leading a “chips 4” pact with Japan, Taiwan and possible South Korea to develop next-generation technologies and manufacturing capacity. China is investing US$1.4 trillion between 2020 and 2025 in a bid to become self-reliant in this technology.

Another big issue is cobalt, which is essential for making lithium batteries for electric vehicles. To secure supply from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which produces 70% of world reserves, China has navigated Congolese politics, lobbying powerful politicians in mining regions. By 2020, Chinese firms owned or had a stake in 15 of the DRC’s 19 cobalt-producing mines.

As China hoards cobalt supplies, the US seeks alternatives. GM is developing its Ultium battery cell, which needs 70% less cobalt than today’s batteries, while Oak Ridge National Laboratory is developing a battery that doesn’t need the metal at all.

Silver linings

As US-China relations have moved from building bridges in 1972 to building walls in 2022, countries will increasingly be forced to choose sides and companies will have to plan supply chains accordingly. Those seeking to trade in both blocs will need to “divisionalise”, running parallel operations.

American companies wanting to serve Chinese consumers will still need to manufacture in China or other nations within that bloc, while Chinese companies will need to do the same in reverse. Interestingly, Chinese companies have been rapidly buying farmland and agriculture-based companies in the US and elsewhere.

Yet though the new supply chains will almost certainly increase costs for western consumers and dampen China’s growth, there will be benefits. Supply chains should be more resilient to future crises and also more transparent, while reduced transportation (and reliance on Chinese coal) should cut carbon emissions. This should help to meet the UN Sustainable Development Goals on environmental and social sustainability.

The cobalt and nanochips examples also show how the US-China rivalry is catalysing innovation. And importantly, global trade will continue growing as countries depend on each other, even as trade links change.

It will certainly take time to find an equilibrium. It took years for the USSR and US to figure out how to co-exist without getting into direct military conflict. Hillary Clinton wrote in 2011 as Secretary of State that “there is no handbook for the evolving US-China relationship”, and that remains the case today.

At any rate, the businesses that thrive in this new environment will likely be those that plan for a divided world with divisional supply chains. The recent Taiwan row will probably not lead to direct military conflict; rather it will reinforce a trend that has been gathering momentum for a decade or more.

ManMohan S Sodhi, Professor of Operations and Supply Chain Management, City, University of London and Christopher S. Tang, Professor of Supply Chain Management, University of California, Los Angeles

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.