Christopher Robertson, Boston University and Wendy Netter Epstein, DePaul University

The Affordable Care Act is back before the U.S. Supreme Court in the latest of dozens of attacks against the law by conservatives fighting what they now perceive to be a government takeover of health care.

Yet, in an odd twist of history, it was Newt Gingrich, one of the most conservative speakers of the House, who laid out the blueprint for the Affordable Care Act as early as 1993. In an interview on “Meet the Press,” Gingrich argued for individuals’ being “required to have health insurance” as a matter of social responsibility.

Over time, he drew on ideas from the conservative Heritage Foundation and Milton Friedman to suggest “that means finding ways through tax credits and through vouchers so that every American can buy insurance, including, I think, a requirement that if you’re above a certain level of income, you have to either have insurance or post a bond.”

If Gingrich laid the blueprint for the ACA, how did the law become a punching bag for right-wing politicians and their appointees in the courts? As experts (Robertson | Epstein) on health law and policy, we will be watching the Supreme Court’s oral arguments on the ACA. If the court strikes it down, we expect that it will force Congress to someday enact a single-payer system, which will be legally invincible. Let us explain.

A bipartisan consensus

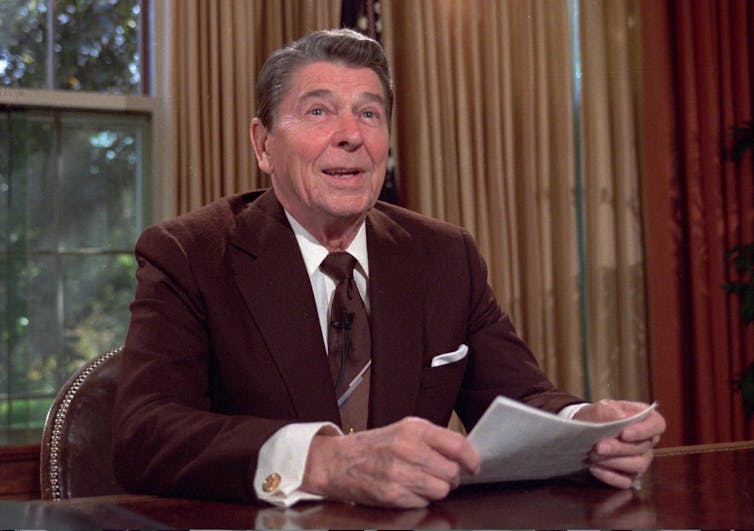

In 1986 President Ronald Reagan signed a law called EMTALA – the Emergency Treatment and Active Labor Act – recognizing that uninsured Americans would get sick and would show up at emergency rooms needing health care.

Reagan and his Republican Senate majority, led by Bob Dole, agreed with their Democratic colleagues in the House that, as a society, we simply cannot turn away fellow Americans to die on the streets. So, to this day, EMTALA requires hospitals to provide emergency health care. But it provides no funding mechanism to do it. Hospitals can try to shift those costs to other payers, or try to go after the patients themselves, who often have no alternative but bankruptcy.

With EMTALA in place, conservatives began to embrace the goal of getting everyone into the insurance system. Conservatives viewed having insurance as a matter of personal responsibility, to avoid passing health care costs on to others.

Conservatives also turned to the Gingrich model, because they long feared the alternative of a single-payer system. What we now call Medicare for All would leave out insurance companies and instead rely on the federal government as the single insurer. Indeed, Reagan got his start in national politics during the 1960s campaigning against the enactment of Medicare. He claimed it would lead to a socialist dictatorship that would “invade every area of freedom we have known in this country.” So, with single-payer off the table, an individual mandate for private health insurance was the conservative solution.

The debate over preexisting conditions

Today, our society has made another moral commitment that insurers cannot turn away the sick. But the market cannot let people wait until they are sick to buy insurance. That would be like buying homeowners insurance when your house is already on fire. If insurers insured only sick people, premiums would have to be exorbitantly high. Rather, insurers must be able to spread the risk of any of us getting sick over a large base of healthy subscribers.

Accordingly, when Republican Mitt Romney was the governor of Massachusetts, he spearheaded a landmark reform that protected patients with preexisting conditions. He also recognized the need to pay for it. Through bipartisan legislative debate and bargaining emerged the individual mandate – a way to encourage people to buy insurance, even when they were healthy.

When Barack Obama was elected president, he initially resisted the idea of an individual mandate. But he lacked the votes for a single-payer approach. In the ACA, he settled on a weak mandate with a low monetary penalty for failure to comply, an expansion of Medicaid through the states, and subsidies so everyone could afford coverage on the private market, just as Newt Gingrich proposed so many years ago.

The right wing pivots

One might have imagined a round of conservative applause, but instead Republicans pivoted to attack mode. Even Gingrich started arguing that the individual mandate was “clearly unconstitutional.” The law ultimately passed with no Republican votes.

The first challenge to the ACA that reached the Supreme Court was in 2012, NFIB v. Sebelius. The issues were the constitutionality of the mandate that people buy insurance or face a penalty, and congressional expansion of state Medicaid coverage for poorer patients.

On the first point, conservative Supreme Court justices decided that Congress lacked the power under the Constitution’s commerce clause to enact the mandate. Although conservative justices normally look to the “original intent” of the founders, the five conservatives ignored the fact that in 1790 and 1798, George Washington and John Adams each signed laws requiring the purchase of health insurance by ship owners and sailors.

Still, Chief Justice Roberts saved the ACA’s mandate, finding it a legitimate exercise of the Constitution’s taxing power; he was joined by the four more liberal justices.

Another key conservative principle is federalism – to retain a central role for the states. The ACA carved out an important role for the states in expanding the state-administered Medicaid program to provide health care for poor Americans. But in the NFIB case, the Court conservatives insisted that states be allowed to opt out.

While on the surface this position seemed like a vindication of states’ rights, in our view, the message to Congress was simple: Don’t involve the states at all. To achieve universal coverage, the federal government needs to do it alone, with a simple federal entitlement, like Medicare.

The 2012 ACA case therefore set a strange precedent. The result is a lopsided reading of constitutional authority. The federal government has a weakened power to work with private businesses and with states to achieve universal coverage. Meanwhile, the federal government has a nearly invincible power to itself tax and spend.

A blank slate?

The battle was not yet over. In 2019, President Donald Trump and congressional Republicans eliminated the tax penalty for going without insurance. A judge in Texas then held that in doing so, Congress inadvertently repealed the entire ACA, including its subsidies, protections for preexisting conditions and expansion of Medicaid. The judge theorized that a tax of zero is not a legal nullity, but rather an unconstitutional and fatal flaw that brings down the entire bill.

That case is the one now in the Supreme Court. The legal arguments are convoluted, depending on whether one part of the Affordable Care Act can be “severed” from the nullified tax. Some conservative legal scholars have panned the challenge.

The conservatives who now control the Supreme Court face an odd dilemma. In the short run, they may strike down the ACA, causing chaos that Congress and the president may not be able fix, given the politics. However, as long as American law reflects the moral commitments to people with emergency health care needs and preexisting conditions, then someday Congress will have to find a way to pay for it.

If conservatives keep killing conservative reforms like the individual mandate and expanding Medicaid through the states, the only alternative left will be a single-payer system, like Medicare for All. Ironically, the Supreme Court has made eminently clear that such a simple tax-and-spend approach is constitutionally invincible.

Christopher Robertson, Professor of Law, Boston University and Wendy Netter Epstein, Professor of Law and Faculty Director of the Jaharis Health Law Institute, DePaul University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.