Brian J. Love, University of Michigan and Julie Rieland, University of Michigan

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the U.S. recycling industry. Waste sources, quantities and destinations are all in flux, and shutdowns have devastated an industry that was already struggling.

Many items designated as reusable, communal or secondhand have been temporarily barred to minimize person-to-person exposure. This is producing higher volumes of waste.

Grocers, whether by state decree or on their own, have brought back single-use plastic bags. Even IKEA has suspended use of its signature yellow reusable in-store bags. Plastic industry lobbyists have also pushed to eliminate plastic bag bans altogether, claiming that reusable bags pose a public health risk.

As researchers interested in industrial ecology and new schemes for polymer recycling, we are concerned about challenges facing the recycling sector and growing distrust of communal and secondhand goods. The trends we see in the making and consuming of single-use goods, particularly plastic, could have lasting negative effects on the circular economy.

Recyclers under pressure

Since March 2020, when most shelter-in-place orders began, sanitation workers have noted massive increases in municipal garbage and recyclables. For example, in cities like Chicago, workers have seen up to 50% more waste.

According to the Solid Waste Association of North America, U.S. cities saw a 20% average increase in municipal solid waste and recycling collection from March into April 2020. Increased trash can be attributed partly to spring cleaning, but most of it is due to people spending greater time at home. Restaurants struggling to survive under COVID-19 restrictions are contributing to the rise in plastic and paper waste with takeout packaging.

Although higher volumes of recyclables are being set on the curb, budget deficits are squeezing recycling programs. Many municipalities are struggling with multimillion-dollar shortfalls. Some communities, such as Rock Springs, Wyoming, and East Peoria, Illinois, have cut recycling programs.

And these stresses are testing a business already faced uncertainty.

Turmoil in scrap markets

The global recycling economy has suffered since 2018 as first China and then other Asian nations banned imports of low-quality scrap – often meaning improperly cleaned food packaging and poorly sorted recyclable materials. As in any business, the value of raw recyclables is linked to supply and demand. Without demand from nations like China, which formerly took up to 700,000 tons of U.S. scrap annually, recyclers have scrambled to stay in business.

The pandemic has boosted prices for some materials. One industry leader told us that between February and May 2020, prices doubled for recycled paper and tripled for recycled cardboard. These shifts reflect higher demand for tissue products and shipping packaging under shelter-in-place orders.

However, he also reported that prices for the most-recycled categories of reclaimed plastics – PET (#1) and PE (#2 and #4) – were at 10-year lows. An influx of cheap oil has driven the raw material cost of oil-derived virgin plastics to their lowest levels in decades, outcompeting recycled feedstocks.

Difficult economics

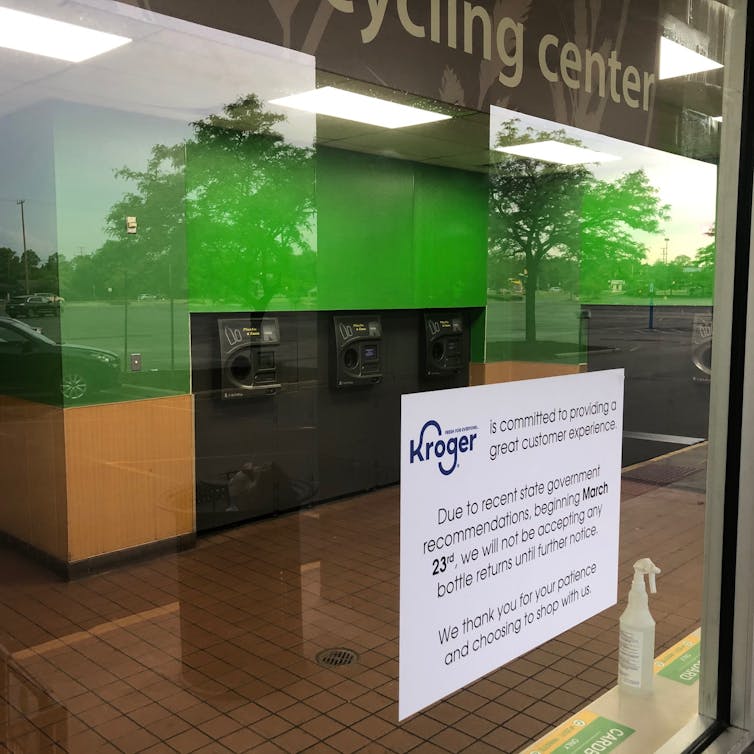

Ideally, revenues from recycling offset municipalities’ costs for collecting and disposing of solid wastes. However, given worker safety concerns, low market prices for scrap materials, a slowed economy and cheaper alternatives for disposal, many communities and businesses across the U.S. have temporarily suspended collection of recyclables and bottle deposits.

Meanwhile, as the commercial sector slowed, the distribution of waste generation changed. As people have spent more time producing waste at home, waste collectors implemented new procedures to protect their employees from infection.

Recycling is a very hands-on process that requires workers to manually sort out items from the collection stream that are unsuitable for mechanical processing. Workers and waste collection companies have raised many safety questions about recycling during the pandemic.

Precautions like social distancing and use of personal protective equipment have become commonplace among waste collectors and sorters, though concerns remain. Sorters are increasingly relying on automation, but implementation can be costly and takes time.

Collections on pause

Based on monitoring since 2017 by the trade publication Waste Dive, nearly 90 curbside recycling programs had experienced or continue to experience a prolonged suspension over the past several years. About 30 of these suspensions have occurred since January 2020.

On a broader scale, it’s not clear how much more waste Americans are currently producing during shutdowns. Commercial and residential waste aren’t directly comparable. For example, a granola bar wrapper thrown away at the office is tallied differently than if discarded at home.

It is also challenging to quantify the effects of the pandemic while it is still unfolding. Historically, waste output from the commercial and industrial sectors has far outweighed the municipal stream. With many offices and business closed or operating at low levels, total U.S. waste production could actually be at a record low during this time. However, data on commercial and industrial wastes are not readily available.

At the California-based Peninsula Sanitary Service, which serves the Stanford University community, total tonnage was down 60% in March. The company attributes this drop to reduced commercial waste, particularly from construction. Similarly, the city of Vancouver, British Columbia, noted a 10% decrease year over year of waste collection levels for April.

More plastic trash

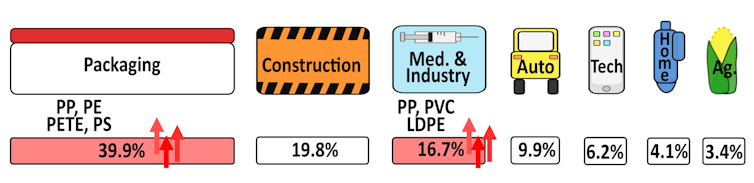

As cities and industries reopen in the coming months, new data will show the pandemic’s effects on consumer habits and waste generation. But regardless of total volume, the mix of materials in household wastes has shifted given the new ubiquity of single-use plastic containers, online shopping packaging and disposable gloves, wipes and face masks. Many of these new staples of pandemic life are made from plastics that are simply not worth recycling if there are any other disposal options.

Today Americans are trying to balance their physical well-being against ever-mounting piles of plastic waste. At a time when reducing and reusing could be dangerous, and recycling economics are unfavorable, we see a need for better options, such as more compostable packaging that is both safer and more sustainable.

[You need to understand the coronavirus pandemic, and we can help. Read The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Brian J. Love, Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, University of Michigan and Julie Rieland, PhD Candidate in Macromolecular Science and Engineering, University of Michigan

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.