Monica Gandhi, University of California, San Francisco

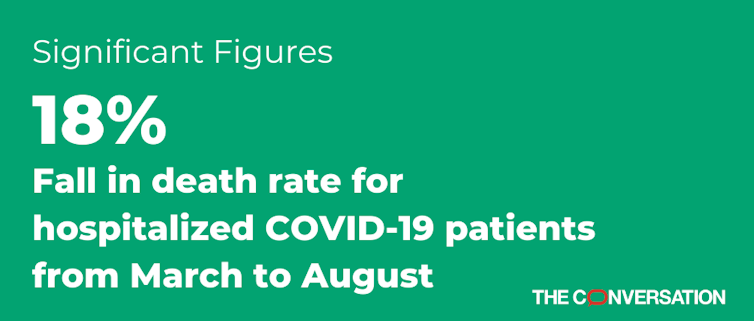

Two large recent studies show that people hospitalized for COVID-19 in March were more than three times as likely to die as people hospitalized for COVID–19 in August.

The first study used data from three hospitals in New York City. The chance of death for someone hospitalized for the coronavirus in those hospitals dropped from an adjusted 25.6% in March to 7.6% in August. The second study, which looked at survival rates in England, found a similar improvement.

Continuous, significant improvement

In March, out of 1,724 people hospitalized for COVID-19 in the three New York hospitals, 430 died. In August, 134 were hospitalized and five died. This change in the raw numbers could be driven by who was arriving at the hospital – if only older people were getting sick, the death rate would be higher, for example – but the researchers controlled for this in their calculations.

To better understand what was causing this decrease in hospitalization death rate, the researchers accounted for a number of possible confounding factors, including the age of patients at hospitalization, race and ethnicity, the amount of oxygen support individuals needed when they got to the hospital and such risk factors as being overweight, smoking, high blood pressure, diabetes, lung disease and so on.

No matter what their specific situation, a person hospitalized in March for COVID-19 was more than three times as likely to die as one hospitalized in August.

The study in England looked at hospitalized coronavirus patients who were sick enough to go to a high-dependency unit (HDU) – one where they were monitored closely for oxygen needs – or the intensive care unit (ICU). As in the New York study, the researchers also accounted for confounding factors, but they calculated survival rates instead of mortality rates.

Looking at 21,082 hospitalizations in England from March 29 to June 21, 2020, the authors found a continuous improvement in survival rates of 12.7% per week in the HDU and 8.9% per week in the ICU. Overall, between March and June the survival rate improved from 71.6% to 92.7% in the HDU and from 58% to 80.4% in the ICU. These increases in survival after hospitalization for the coronavirus in England mirrored the changes in New York City.

Better treatments and better care are responsible

The main reason researchers think coronavirus patients are doing better is simply that there are now effective treatments for the virus that didn’t exist in March.

I am a practicing infectious disease doctor at the University of California, San Francisco, and I have witnessed these improvements firsthand. Early on, my colleagues and I had no idea how to treat this brand-new virus that burst onto the scene in late 2019. But over the spring, large studies tested different treatments for COVID-19 and we now use an antiviral called remdesivir and a steroid called dexamethasone to treat our hospitalized coronavirus patients.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Along with these new treatments, physicians gained experience and learned simple techniques that improved outcomes over time, such as positioning a patient with low oxygen in a prone position to help distribute oxygen more evenly throughout the lungs. And as time has gone on, hospitals have become better prepared to handle the increased need for oxygen and other specialized care for patients with the coronavirus.

Though improvements in care and effective drugs like remdesivir and dexamethasone have helped greatly, the virus is still very dangerous. People with severe cases can suffer prolonged symptoms of fatigue and other debilitating effects. Therefore, other treatments should be and are still explored.

Public health measures help too

Treatments have undoubtedly gotten better. But the authors of the New York City study specifically mention that public health measures not only led to the plummeting hospitalization rates – 1,724 in March vs. 134 in August – but might have helped lower death rates too.

My own research proposes that social distancing and face coverings may reduce how much virus people are exposed to, overall leading to less severe cases of COVID–19. It is important to continue to follow public health measures to help us get through the pandemic. This will slow the spread of the virus and help keep people healthier until a safe and effective vaccine is widely available.

Monica Gandhi, Professor of Medicine, Division of HIV, Infectious Diseases and Global Medicine, University of California, San Francisco

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.