Catesby Holmes, The Conversation

The assassination of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse risks destabilizing the Caribbean country, which was already in crisis over alarmingly high violence and Moïse’s increasingly undemocratic behavior.

Here’s some essential background on Haiti, starting with the painful history that underlies so much of Haiti’s modern struggles.

1. France’s ‘extortion’

Haiti officially declared its independence from colonizer France in 1804 after a revolutionary war staged by enslaved laborers and inspired by the American Revolution.

But the French “never quite gave up on reconquering their former colony,” according to Marlene Daut, a historian of Haiti at the University of Virginia.

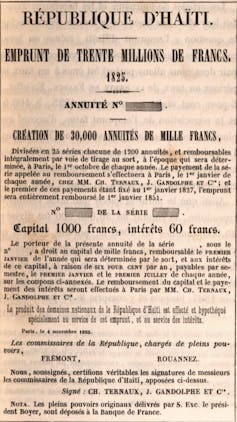

Between 1814 and 1825, France sent repeated delegations to Haiti to negotiate with its new leaders about restoring some formal relationship with France. When that failed, King Charles X in 1825 decreed that France would recognize Haitian independence, but only if the new country paid France the exorbitant price of 150 million francs.

“The sum was meant to compensate the French colonists for their lost revenues from slavery,” says Daut. “Rejection of the ordinance almost certainly meant war.”

Under threat of violence, the Haitian leader, Jean-Pierre Boyer, signed a document agreeing to pay France “in five equal installments … the sum of 150,000,000 francs, destined to indemnify the former colonists.”

The deal forced Haiti to take out enormous loans. The young nation defaulted on them, despite Boyer’s levying punishing taxes on the Haitian people in his failed effort to pay them off. Its debt to France took 122 years to pay off.

“This was not diplomacy,” Daut says of France’s demand for payment. “It was extortion.”

2. US occupation

By the 20th century, the United States was the foreign country exerting undue control over Haiti’s ailing economy.

It did so through a combination of military might, political maneuvering and private investment, writes Florida State University Professor Vincent Joos, who studies Haiti’s economy.

The American military occupied Haiti from 1915 to 1934 and controlled its government. During that period, the U.S. designed Haiti’s economic and social policies to attract foreign investment.

“In practice, that meant keeping Haitian wages, corporate taxes and tariffs low,” says Joos. “In exchange, the theory went, foreign investment would bring infrastructure development and jobs, benefiting all Haitians.”

Part of the Americans’ plan worked: American agricultural firms did begin profitably growing cash crops like coffee, bananas and sugar in Haiti in the 1910s and 1920s. Later, U.S. businesses and military agencies established rubber plantations and textile factories there.

But Haiti’s export-focused economic model hasn’t benefited its people.

“After decades of extremely business-friendly policies, three-quarters of Haitians still live on less than US$2.40 a day,” writes Joos.

3. The earthquake

On Jan. 12, 2010, a massive earthquake left Haiti in shambles – physically, economically and politically. Upwards of 300,000 people were killed and nearly 1.5 million of Haiti’s 10 million people instantly became homeless.

Researcher Joseph Jr Clormeus was in Port-au-Prince that day and survived the earthquake. Some of his colleagues “lost their lives while others were having limbs amputated to escape certain death under the rubble,” he recalls. “Outside, corpses littered the streets of the capital.”

Last year, on the 10th anniversary of the quake, Clormeus and co-authors Jean-François Savard and Emmanuel Sael wrote a story assessing Haiti’s stalled recovery.

“Haiti hasn’t recovered from this disaster, despite billions of dollars being spent in the country,” they concluded.

One big problem, according to their analysis: Haiti’s government was weak after decades of dictatorship in the 20th century and a series of unstable democratic administrations in the 21st.

Clormeus, Savard and Sael also blame the international-led disaster recovery effort for Haiti’s continued struggles.

After the earthquake, hundreds of foreign aid agencies and international organizations like the Red Cross flooded into Haiti, intending to help. But “there was no coordination in the interventions of friendly countries in order to optimize the efforts on behalf of the victims,” write Clormeus, Savard and Sael.

The international community “failed to meet a humanitarian challenge of such magnitude.”

4. Austerity and foreign influence

The international community has also failed in its efforts to alleviate the privation and struggle of the Haitian people. The average income is $5 a day, and many people live on much less.

Haiti’s government, likewise, remains cash-strapped. It is frequently unable to provide basic services like trash collection or to hold timely elections.

The country “runs on borrowed funds,” says Florida State’s Vincent Joos.

Loans sometimes fund 20% of Haiti’s national budget. That gives lending institutions like the International Monetary Fund outsized influence on domestic policies. In 2018, deadly protests erupted over gas prices after Haiti’s creditors recommended ending petroleum subsidies.

The International Monetary Fund’s “de facto control over the economy” of Haiti dates back decades – as do popular uprisings against it, says Joos.

5. Crisis under Moïse

Long-standing discontent with Haiti’s unequal economy and its ineffective government grew during President Jovenel Moïse’s 4 ½-year term.

Moïse’s killing followed months of sustained protests demanding his resignation after he refused to vacate the presidency, which was meant to end in February. Moïse said he planned to modify the Haitian constitution to allow him to stay in office even longer.

“Moïse had been ruling by decree,” Tamanisha John, a Caribbean studies scholar at Florida International University, explained after the president’s assassination. “He effectively shuttered the Haitian legislature by refusing to hold parliamentary elections scheduled for January 2020 and summarily dismissed all of the country’s elected mayors in July 2020, when their terms expired.”

Moïse – the chosen successor of Haiti’s unpopular last president, Michel Martelly – lost the trust of the Haitian people early, according to John. In 2017, the frst year of his administration, Moïse was implicated in an embezzlement scandal in which at least $700,000 of public money was allegedly funneled into the banana business he owned.

Though Moïse is dead, his party retains power. Prime Minister Claude Joseph, appointed by Moïse on an interim basis in April after the sitting prime minister resigned, controls Haiti for now. The country, he says, is in a “state of siege.”

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]

Catesby Holmes, International Editor | Politics Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.