Matthew McMahan, Emerson College

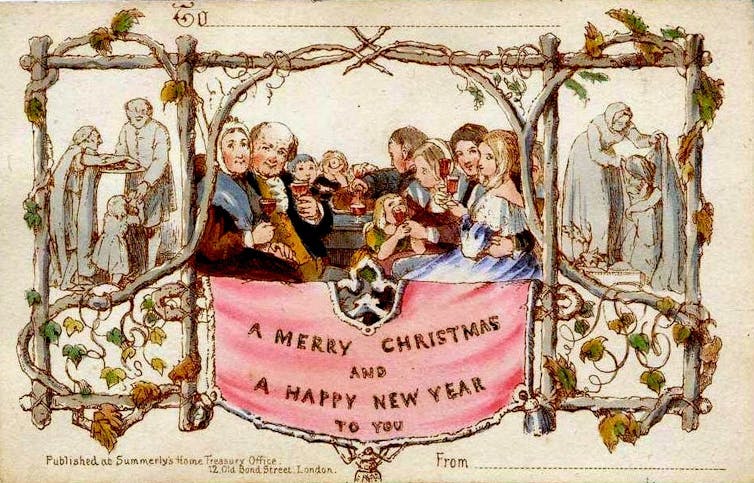

The first Christmas card was, perhaps predictably, one of good cheer. The concept is commonly credited to Sir Henry Cole, the founder of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

To spare himself the stress of responding to the all-too-many Christmas letters he received from friends, Cole commissioned an artist to create 1,000 engraved holiday cards in 1843. Featuring a prosperous family toasting the holidays, the image was flanked on both sides by images of kindly souls engaging in acts of charity. A caption along the bottom read, “A Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to You.”

But given the end to a bruising year of a worldwide pandemic, enormous economic suffering and a venomous election season, a classic and macabre Charles Addams cartoon might feel more appropriate in 2020. The Addams family gazes outside a bay window to see snow falling while their neighbors decorate, deliver gifts, and build snowmen. Gomez Addams lachrymosely sighs, “Suddenly I have a dreadful urge to be merry.”

The comic captures the repressive side of the phrase “Have a Merry Christmas”: the push to be hopeful during the holidays, even when it does not feel right.

I am a theater historian who focuses on the history of comedy. Particularly, I’m interested in comedy as a mode of communication and how it uniquely conveys information.

Lately, I’ve been curious to see how recent holiday cards have dealt with the tensions of the year – and how greeting cards during other eras of struggle handled the holidays. From a cursory review, it’s clear other difficult times have revealed a similar instinct to acknowledge the incongruence of strife mixed with the season of joy.

Macabre with the merry

In the book “American Holiday Postcards, 1905-1915: Imagery and Context,” author Daniel Gifford writes, “Because holidays are socially constructed, a certain quorum of rituals, meanings, symbols, etc. is shared among the participants in order to give the holiday shape and for participants to understand their significance.”

Over time, these rituals have often taken the form of tokens of merriment such as beatific cherubs or velvet-clad jolly Saint Nicks. They are often ensnared by floral patterns, holly bushes, firs, pines and wreaths. They evince saccharine families, dressed alike, clinging to each other with an almost enviable, and sometimes believable, warmth.

The cards are usually rife with sentimentality, and the imagery tends toward the cliché. The combination of these two – the sentimental and the cliché – offers up the perfect opportunity to make jokes. A tendency in many comic holiday cards is to bring up the circumstances of the day and how the state of affairs disrupt the usual joviality of the season.

The side effect is that these joke cards preserve history in a playful way. Although the chief objective of any joke or gag is to entertain, because they are meant to evoke an emotional response – a laugh, a smile or even a groan – they also capture what the joke teller and his or her audience may feel about the holidays.

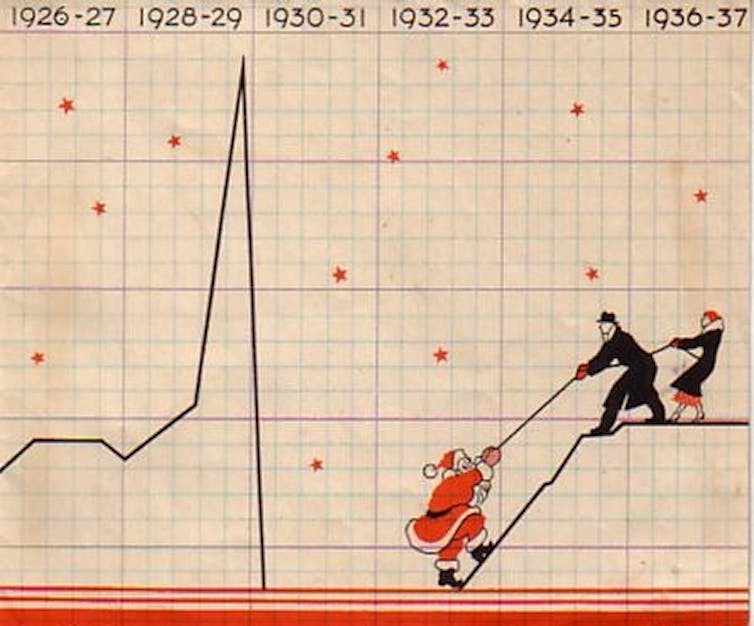

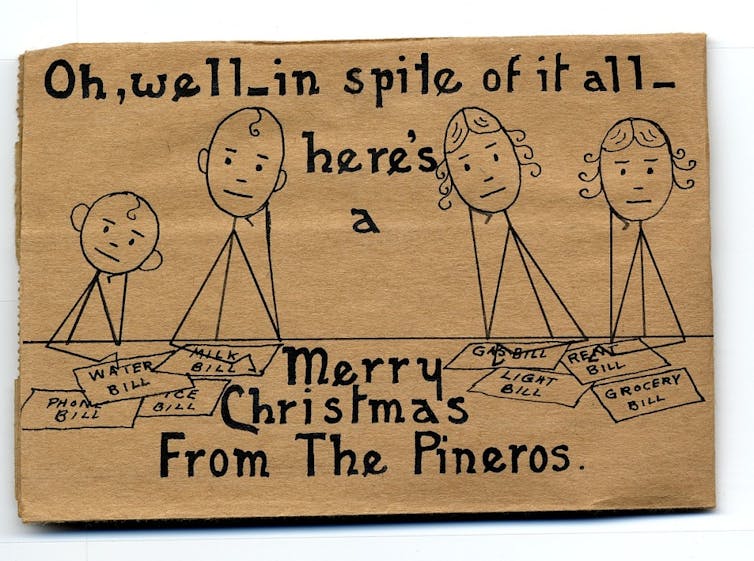

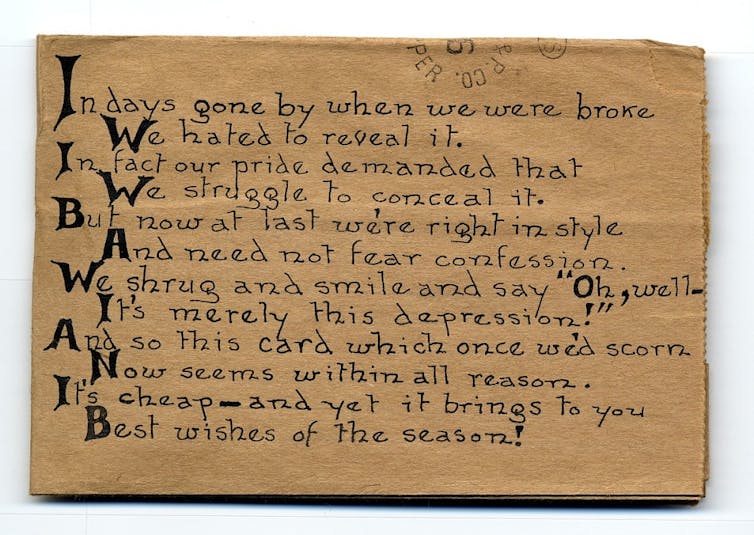

The timely Christmas card, then, infuses the typical – holiday imagery – with the topical – what’s going on at that specific moment in time. The Great Depression is a prime example.

This homemade card by a financially struggling family tugs on the heartstrings in a different way than holiday cards usually do, but still captures the droll irony of the moment.

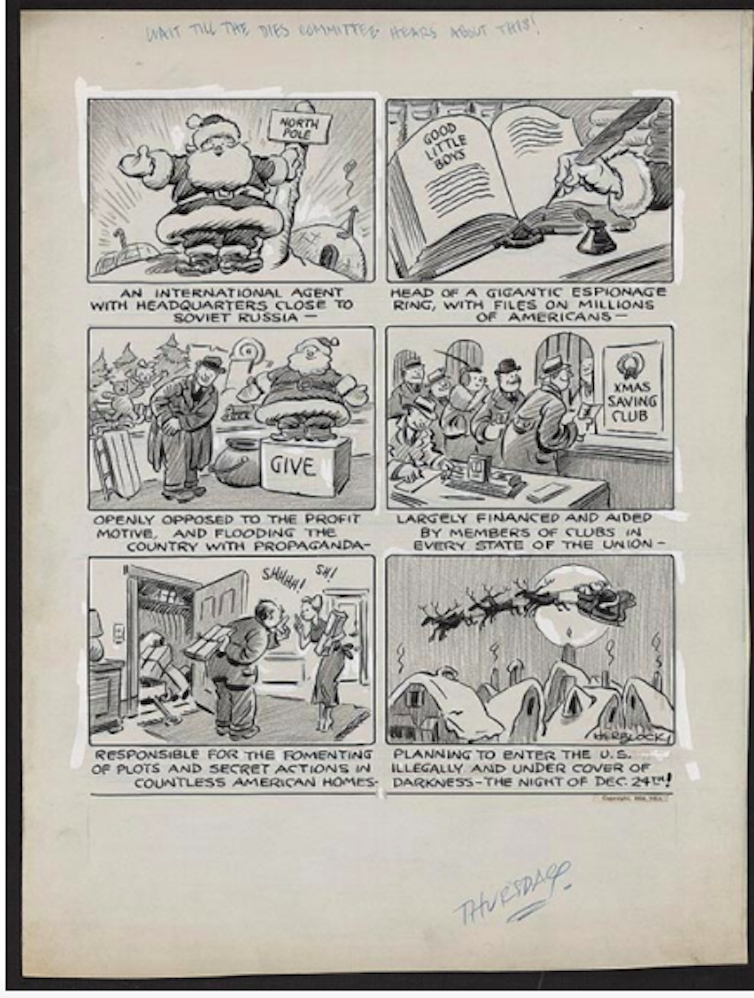

The cartoonist Herbert Block was unafraid of addressing political injustice in his yearly holiday drawings. In this 1938 cartoon located in the Library of Congress, he questions whether the Dies Committee – also known as the The House Committee on Un-American Activities – would find Santa Claus to be un-American.

A funny end to a lousy year

Today, in the spirit of Jon Stewart, the comedian and political commentator, we’ve all become ironists, wielding a cutting perspective on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram alike. These mediums spur creativity and competition with the elusive promise of making viral – a term we perhaps should reconsider! – the most clever or irreverent gag.

This certainly occurred before the pandemic, but the events of the last year have allowed Americans to mock the usual holiday imagery by acknowledging that this Christmas is not merry, at least not in the usual way.

One of my favorites is a 2020 card that adds a sardonic twist to the cozy familiarity of Charles Schultz’s Peanuts.

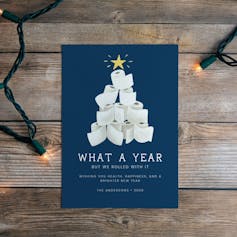

There are other great ones out there where the clever meet the current mood. Take one that addresses the nation’s run on toilet paper from Dottie & Caro.

And see this one from Saucy Avocado that plays on the night before Christmas magic.

So, although many families all over the world are certainly experiencing a period of great strife and loneliness, that doesn’t mean the holiday greetings have to skirt the sad. Rather, a touch of irreverence enables these cards to mark the anxieties and worries of the now with the spirit of a different, and still meaningful, sort of merriment.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Matthew McMahan, Assistant Director, Comedic Arts, Emerson College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.