The Senate voted 84-15 to confirm economist Janet Yellen as U.S. Treasury secretary on Jan. 25, and her in tray will require every ounce of her vast experience to pilot the economy through a daunting confluence of challenges.

How the U.S. manages the economic recovery from COVID-19, the financial risks from climate change and inequality together will determine the chances of American prosperity over the coming decades.

First, Yellen will need to ensure that economic stimulus packages produce a job-rich recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. She can help guide the U.S. to the sweet spot of immediate growth that also puts the country on the path toward a cleaner, more resilient future. This means measures that steer investment and job creation in the sectors of the future, including clean energy, energy efficiency, clean transport and resilient agriculture.

Second, she will have a crucial role in orchestrating a total government approach to climate risk and resilience. That includes working across every department and agency involved in the regulation, policy and management of financial markets and the economy.

Third, COVID-19 has revealed the extent of the nation’s lack of resilience. With climate shocks only expected to intensify, Yellen’s role in the nation’s recovery also means confronting inequality.

Yellen, a former Federal Reserve chair and professor of economics, is respected by her peers and international financial institutions, and she will be in a position to persuade banks and businesses to take climate change seriously. But there will be no honeymoon.

I have been involved in international sustainable development and climate diplomacy for years as a former World Bank vice president and senior U.N. official, and I see several ways Yellen can use the power of the U.S. Treasury to lay the foundation for real and lasting progress on climate change.

Finding a way to put a price on carbon

The good news is that Yellen has a keen understanding of the issues surrounding climate change and their interplay, and the roles that financial regulators and economic leaders can play.

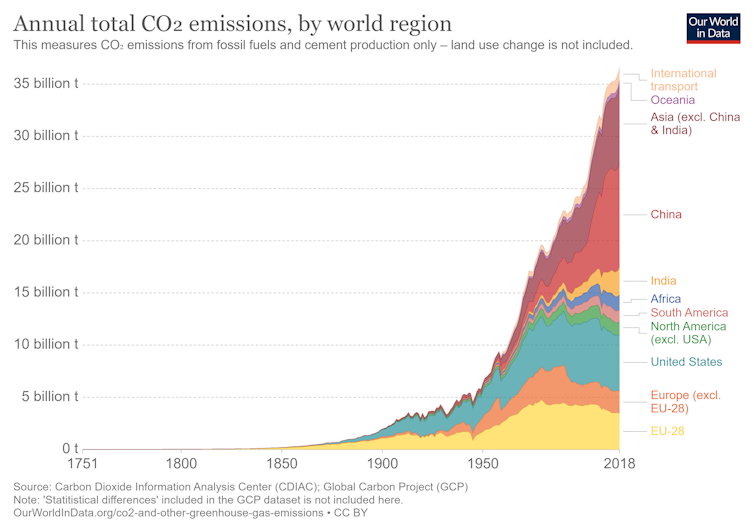

For example, she is sensitive to the need to put a price on carbon pollution to help curb emissions. The cost of that pollution today is borne by the public, from bad air quality to extreme weather and sea level rise. A carbon price, coupled with incentives and standards, will speed up the drive to clean technologies by making polluting expensive for companies and risky for their investors.

During her confirmation hearing, Yellen talked about climate change as a priority, describing it as an existential threat and a risk to the financial system. In response to senators’ questions, she wrote that she believes “we cannot solve the climate crisis without effective carbon pricing” and that President Joe Biden “supports an enforcement mechanism that requires polluters to bear the full cost of the carbon pollution they are emitting.”

Last year, she said that she could see a way forward with bipartisan support for a carbon tax that charges polluters for their carbon emissions and redistributes the proceeds to Americans in quarterly payments, a move that would help low-income residents in particular as the world shifts to cleaner energy. After years leading the Climate Leadership Coalition, a bipartisan platform advocating for effective carbon pricing, she has the credibility to engineer progress on such a hot-button issue.

More of her views can be seen in the recommendations of a task force Yellen co-chaired in 2020 with Mark Carney, the former head of the Bank of England, for the economic think tank the G30. The task force recommended that to achieve net-zero emissions, all countries need to price carbon appropriately; shift incentives for companies and their executives so sustainability is a priority; and harness markets to speed up the rate of transition away from fossil fuels.

The task force also recommended that countries set up Carbon Councils, independent government bodies that would “supervise and oversee markets to ensure the delivery of real, positive planetary outcomes and dramatically lowered greenhouse gas emissions.

That advice may be redundant with the appointment of Gina McCarthy in the new role of national climate advisor.

Bringing climate risk awareness to the financial system

Yellen has an important role to play and a mechanism already at hand: the Federal Stability Oversight Council. It was created by the 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act to identify risks to U.S. financial stability and respond to emerging threats. The council is chaired by the Treasury secretary and comprises all major federal financial regulators. This is a place where Yellen can insert climate risk awareness into the U.S. finance’s central nervous system.

In the past few years, other countries’ central banks have both introduced climate-risk stress tests to determine financial institutions’ vulnerability to climate change and imposed rules around exposure to fossil fuels. The U.S. lags, but there is momentum for Yellen and the FSOC to build on.

The Federal Reserve has already identified climate change as a risk to financial stability, and in December, it joined the Network for Greening the Financial System, a global leadership group of central banks and financial regulators.

Using international aid to rebuild soft power

Yellen will also be coordinating efforts across the government to most effectively manage U.S. global financial engagement on climate change and other risks.

She has unique reach through international finance. The Treasury Department can influence USAID, which provides aid to countries in need; the Millennium Challenge Corp., which supports economic development to reduce poverty; the Export-Import Bank, which provides financing to boost U.S. exports; the U.S. Trade and Development Agency, which helps connect U.S. companies with infrastructure projects overseas; and the potentially powerful International Development Finance Corp. In the right hands, the tools of the DFC can help channel funding to green and resilient infrastructure in low-income countries.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Financing climate-friendly projects could help the U.S. reclaim both soft power overseas and its international climate leadership. However, support for pandemic recovery and climate resilience cannot mire low- and middle-income countries in more debt. The debt crisis, worsened by COVID-19, demands careful choreography among international financial institutions, European allies, China, central banks and private financiers. And it will need some fresh thinking.

The Treasury secretary’s in tray is daunting in its complexity. There’s a lot riding on Janet Yellen’s shoulders, head and heart.

This article has been updated with the Senate voting 84-15 to confirm Yellen as U.S. Treasury secretary.

Rachel Kyte, Dean of the Fletcher School, Tufts University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.