David Barnhart, University of Southern California

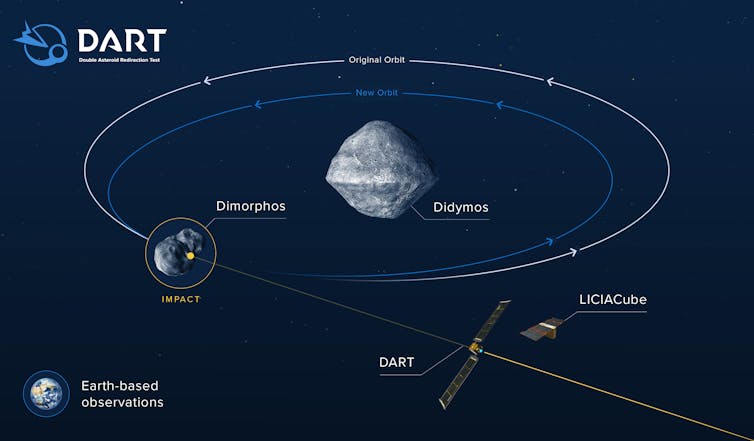

NASA recently crashed a spacecraft into an asteroid in an attempt to push the rocky traveler off its trajectory. The Double Asteroid Redirection Test – or DART – was meant to test one potential strategy for preventing an asteroid from colliding with Earth. The collision occurred on Sept. 27, 2022, and on Oct. 11, 2022, NASA announced that the mission had successfully changed the orbit of the asteroid Dimorphos. David Barnhart is a professor of astronautics at the University of Southern California and director of the Space Engineering Research Center there. He watched NASA’s live stream of the successful mission and explains what happened.

1. What do the images from DART show?

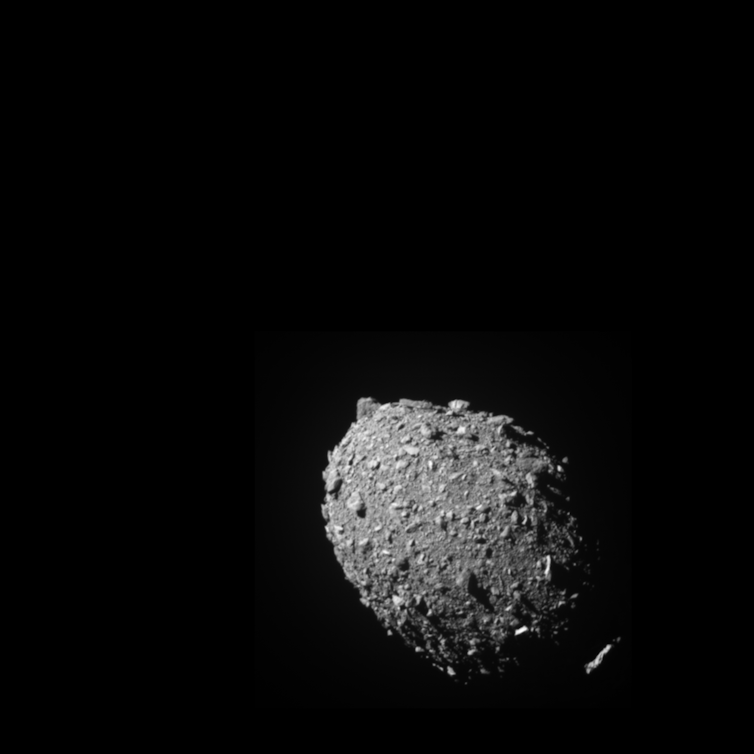

The first images, taken by a camera aboard DART, show the double asteroid system of Didymos – about 2,500 feet (780 meters) in diameter – being orbited by the smaller asteroid Dimorphos, which is about 525 feet (160 meters) long.

As the targeting algorithm on DART locked onto Dimorphos, the craft adjusted its flight and began heading toward the smaller of the two asteroids. The image taken at 11 seconds before impact and 42 miles (68 kilometers) from Dimorphos shows the asteroid centered in the camera’s field of view. This meant the targeting algorithm was fairly accurate and the craft would collide right at the center of Dimorphos.

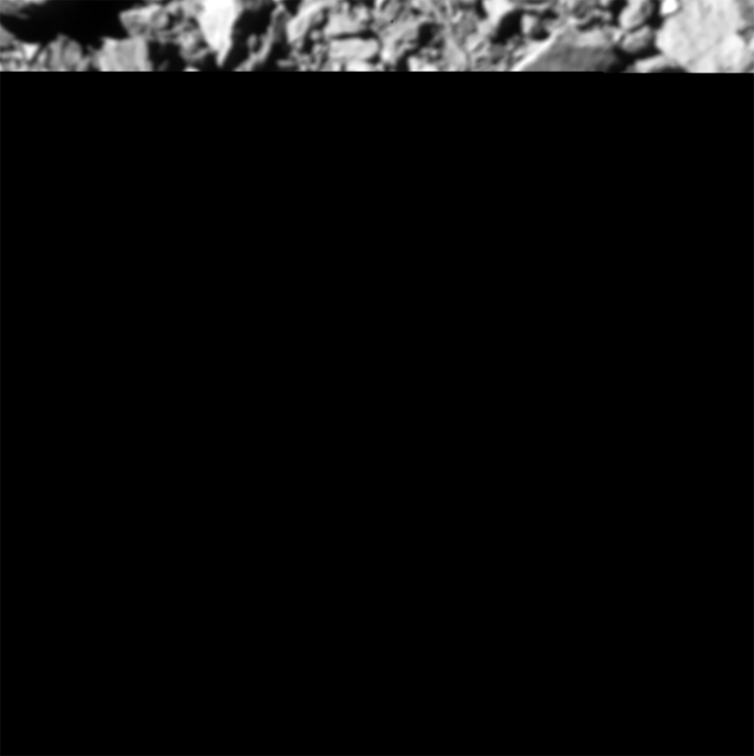

The second-to-last image, taken two seconds before impact, shows the rocky surface of Dimorphos, including small shadows. These shadows are interesting because they suggest that the camera aboard the DART spacecraft was seeing Dimorphos directly on but the Sun was at an angle relative to the camera. They imply the DART spacecraft was centered on its trajectory to impact Dimorphos at the moment, but it’s also possible the asteroid was slowly rotating relative to the camera.

The final photo, taken one second before impact, only shows the top slice of an image, but this is incredibly exciting. The fact that NASA received only part of the image suggests that the shutter took the picture but DART, traveling at around 14,000 mph (22,500 kph), was unable to transmit the complete image before impact.

2. What was supposed to happen?

The point of the DART mission was to test whether it is possible to deflect an asteroid with a kinetic impact – by crashing something into it. NASA used the analogy of a golf cart hitting the side of an Egyptian pyramid to convey the relative difference in size between tiny DART and Dimorphos, the smaller of the two asteroids. Prior to the test, Dimorphos orbited Didymos in just under 12 hours. NASA expects the impact to shorten Dimorphos’ orbit by about 1%. Though small, if done far enough away from Earth, a nudge like this could potentially deflect a future asteroid headed toward Earth just enough to prevent an impact.

3. Did it work?

The last bits of data that came from the DART spacecraft right before impact showed that it was on course. The fact that the images stopped transmitting after the target point was reached was the first sign of success.

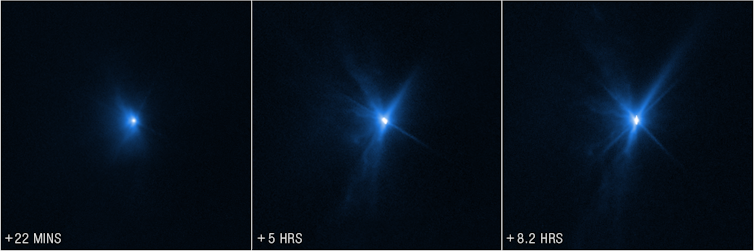

Fifteen days before the impact, DART released a small satellite with a camera that was designed to document the entire impact. The small satellite has been sending photos of the impact back to Earth during early October 2022. A number of Earth-based telescopes as well as some satellites in orbit, including Hubble and James Webb, were watching Didymos at the time of the impact as well.

Using data from these telescopes taken at the time of impact as well as over the following weeks, the DART team at NASA has been able to calculate just how much the impact deflected the orbit of Dimorphos. Before DART, it took 11 hours and 55 minutes for the smaller moonlet to orbit the larger asteroid Didymos. The energy from the impact shortened Dimorphos’s orbit by 32 minutes – showing the impact to be more than 25 times more effective than NASA’s conservative goal of 72 seconds.

4. What does the test mean for planetary defense?

I believe this test was a great proof-of-concept for many technologies that the U.S. government has invested in over the years. And importantly, it proves that it is possible to send a craft to intercept with a minuscule target millions of miles away from Earth and change its orbit. DART has been a great success.

Over the course of the next months and years, researchers will learn just how efficient the impact was – and most importantly, whether this type of kinetic impact can actually move a celestial object ever so slightly at a great enough distance to prevent a future asteroid from threatening Earth.

This is an updated version of a story first published on Sept. 27, 2022.

David Barnhart, Professor of Astronautics, University of Southern California

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.