Thomas Martin, College of the Holy Cross

In ancient Athens, solely the very wealthiest individuals paid direct taxes, and these went to fund the city-state’s most vital nationwide bills – the navy and honors for the gods. While as we speak it may sound astonishing, most of those high taxpayers not solely paid fortunately, however boasted about how a lot they paid.

Money was simply as vital to the ancient Athenians as it is to most individuals as we speak, so what accounts for this enthusiastic response to a big tax invoice? The Athenian monetary elite felt this manner as a result of they earned a useful payback: public respect from the different residents of their democracy.

Modern wants, trendy funds

Athens in the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. had a inhabitants of free and enslaved individuals topping 300,000 people. The economic system largely focused on international trade, and Athens wanted to spend giant sums of cash to maintain issues buzzing – from supporting nationwide protection to the countless public fountains always pouring out consuming water throughout the metropolis.

Much of this earnings got here from publicly owned farmland and silver mines that had been leased to the highest bidders, however Athens additionally taxed imports and exports and collected charges from immigrants and prostitutes in addition to fines imposed on losers in lots of court docket circumstances. In common, there have been no direct taxes on earnings or wealth.

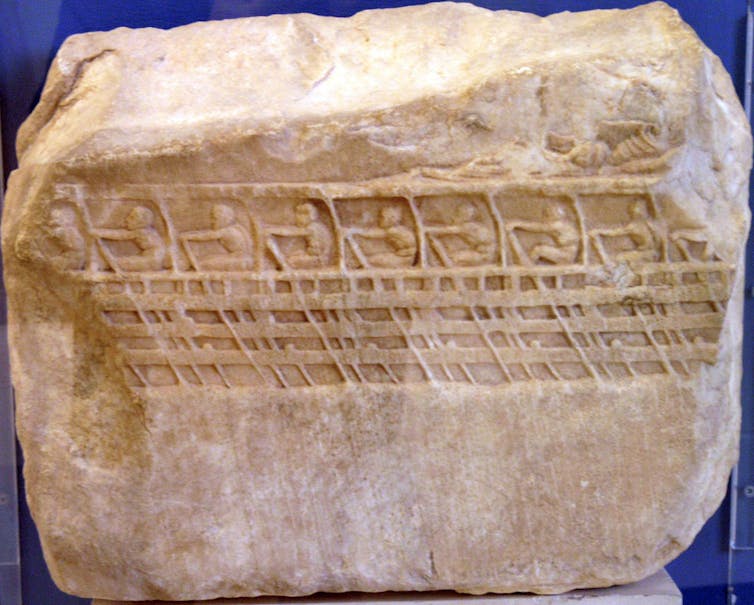

As Athens grew into a global energy, it developed a big and costly navy of a number of hundred state-of-the-art wooden warships called triremes – actually which means three-rowers. Triremes price big quantities of cash to construct, equip and crew, and the Athenian monetary elites had been the ones that paid to make it occur.

The high 1% of male property house owners supported the saving or salvation of Athens –referred to as “soteria” – by performing a particular form of public service referred to as “leitourgia,” or liturgy. They served as a trireme commander, or “trierarch,” who personally funded the working prices of a trireme for a complete 12 months and even led the crew on missions. This public service was not low cost. To fund their liturgy as a trierarch, a wealthy taxpayer spent what a talented employee earned in 10 to twenty years of regular pay, however as a substitute of dodging this duty, most embraced it.

Running warships was not the solely duty the wealthy needed to nationwide protection. When Athens was at battle – which was most of the time – the rich needed to pay contributions in cash referred to as “eisphorai” to finance the citizen militia. These contributions had been primarily based on the worth of their property, not their earnings, which made them in a way a direct tax on wealth.

To please the gods

To the ancient Athenians, bodily army may was solely a part of the equation. They additionally believed that the salvation of the state from outdoors threats relied on a much less tangible however equally essential and expensive supply of protection: the favor of the gods.

To hold these highly effective however fickle divine protectors on their aspect, the Athenians constructed elaborate temples, carried out giant sacrifices and organized energetic public spiritual festivals. These huge spectacles featured musical extravaganzas and theater performances that had been attended by tens of thousands of people and had been vastly costly to throw.

Just as with trieremes, the richest Athenians paid for these festivals by fulfilling competition liturgies. Serving as a chorus leader, for instance, meant paying for the coaching, costumes and dwelling bills for big teams of performers for months at a time.

Proud to be paying

In the U.S. as we speak, an estimated one out of every six tax dollars is unpaid. Large corporations and rich citizens do the whole lot they can to reduce their tax invoice. The Athenians would have ridiculed such conduct.

None of the monetary elite of ancient Athens prided themselves on scamming the Athenian equal of the IRS. Just the reverse was true: They paid, and even boasted in public – in truth – that they typically had paid more than required when serving as a trierarch or chorus leader.

Of course, not each member of the superrich at Athens behaved like a patriotic champion. Some Athenian shirkers tried to escape their liturgies by claiming different individuals with extra property must shoulder the price as a substitute of themselves, however this tried weaseling out of public service by no means turned the norm.

[The Conversation’s science, health and technology editors pick their favorite stories. Weekly on Wednesdays.]

So what was the reasoning behind this civic, taxpaying satisfaction? Ancient Athenians weren’t solely opening their wallets to advertise the frequent good. They had been relying on earning a high return in public esteem from the investments in their community that their taxes represented.

This social capital was so priceless as a result of Athenian tradition held civic obligation in excessive regard. If a wealthy Athenian hoarded his wealth, he was mocked and labeled a “greedy man” who “borrows from guests staying his house” and “when he sells wine to a friend, he sells it watered!”

Social wealth, not financial riches

The social rewards that tax funds earned the wealthy had lengthy lives. A liturgist who financed the refrain of a prize-winning drama may build himself a spectacular monument in a conspicuous downtown location to announce his excellence to all comers all the time.

Above all, the Athenian wealthy paid their taxes as a result of they craved the social success that got here from their compatriots publicly figuring out them as citizens who are good because they are useful. Earning the honorable title of a helpful citizen may sound tame as we speak – it didn’t increase Pete Buttigieg’s presidential campaign regardless that he describes his political position as “trying to make myself useful” – however in a letter to a Hebrew congregation in Rhode Island written in 1790, George Washington proclaimed that being “useful” was an invaluable part of the divine plan for the United States.

So, too, the Athenians infused that designation with immense energy. To be a wealthy taxpayer who was good and helpful to his fellow residents counted much more than cash in the financial institution. And this invaluable public service profited all Athenians by conserving their democracy alive century after century.

Thomas Martin, Professor of Classics, College of the Holy Cross

This article is republished from The Conversation below a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.