W. Joseph Campbell, American University School of Communication

The Republican pollster Frank Luntz warned on Twitter and elsewhere the opposite day that if preelection polls on this yr’s presidential race are embarrassingly wrong again, “then the polling industry is done.”

It was fairly the forecast.

While it’s potential the polls will misfire, it’s exceedingly unlikely that such failure would trigger the opinion analysis trade to implode or wither away. One cause is that election polls signify a sliver of a well-established, multibillion-dollar trade that conducts innumerable surveys on coverage points, shopper product preferences and different nonelection matters.

If opinion analysis had been so weak to election polling failure, the sphere seemingly would have disintegrated way back, after the successive embarrassments of 1948 and 1952. In 1948, pollsters confidently – however wrongly – predicted Thomas E. Dewey would simply unseat President Harry Truman. In 1952, pollsters turned cautious and anticipated a detailed race between Dwight Eisenhower and Adlai Stevenson. Eisenhower gained in a landslide that no pollster foresaw.

“Predictive failure,” I observe in my newest guide, “Lost in a Gallup: Polling Failure in U.S. Presidential Elections,” clearly “has not killed off election polling.”

So what, then, accounts for its tenacity and resilience? Why are election polls nonetheless with us, regardless of periodic flubs, fiascoes and miscalls? Why, certainly, are many Americans so intrigued by election polling, particularly throughout presidential campaigns?

Illusion of precision

The causes are a number of, and never surprisingly tied to deep currents in American life. They embrace – however go effectively past – a simplistic clarification that individuals need to know what’s going to occur.

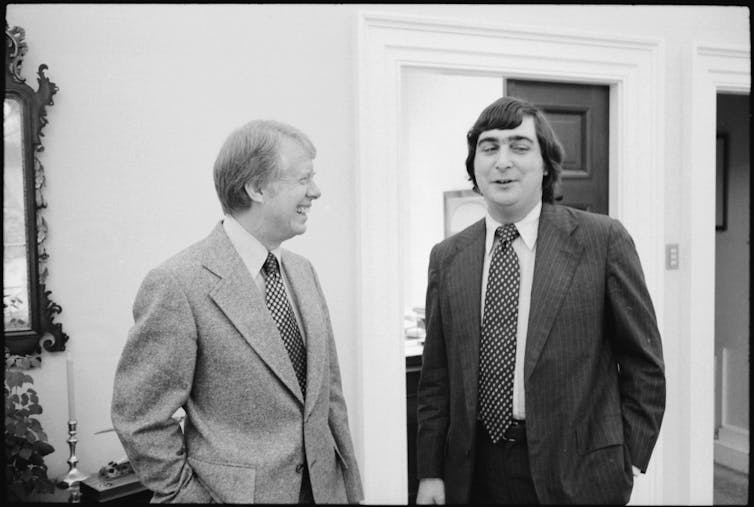

Patrick Caddell, the personal pollster for President Jimmy Carter, spoke to that tendency years ago, saying, “Everyone follows polls because everything in American life is geared to the question of who’s going to win – whether it’s sports or politics or whatever. There’s a natural curiosity.”

More substantively, election polling initiatives the sense, or phantasm, of precision, which holds appreciable enchantment in troubled instances.

A hunger for certainty runs deep, particularly in journalism, the place reporters steadily encounter ambiguity and evasion. Since the mid-Seventies, massive information organizations resembling The New York Times and CBS News have carried out or commissioned their very own election polls. And experiences of crude preelection polls have been present in American newspapers printed as way back as 1824.

These days, polls information, drive and assist repair information media narratives about presidential elections. They are vital to shaping standard knowledge in regards to the competitiveness of these races.

Public unaware of polling flubs

But polls have an uneven record in trendy presidential elections – which, paradoxically, has contributed to their resilience.

Americans are principally oblivious to that report. They could also be vaguely acquainted with the “Dewey defeats Truman” debacle of 1948. And they might recall that election polls in 2016 veered off course in key Midwestern states, disrupting expectations that Hillary Clinton would win the presidency.

But different circumstances, such because the unexpected landslide of 1952 or the close election that wasn’t in 1980, are not typically recalled. So polling is no less than considerably shielded from reproach by unfamiliarity with its uneven efficiency report over time.

Of course, election polls are not all the time in error. They can redeem themselves, which is one other worth in American life.

Horse races to excessive wires

Analogies from the sporting world additional assist to elucidate polling’s tenacity.

Election polling, and its emphasis on who’s forward and who’s sinking, lengthy has been likened to a horse race – a metaphor not all the time agreeable to pollsters. Archibald Crossley, a pioneer of recent opinion analysis, revealed as a lot earlier than the debacle of 1948, in a letter to his good friend and rival pollster, George Gallup.

“I have a distinct impression,” Crossley wrote, “that polls are still thought of as horse-race predictions, and it seems to me that we might be able to do something jointly to prevent such a reputation.”

Crossley’s “distinct impression” endures. Polls, and the coverage of polls, nonetheless invite comparisons to the horse race.

A greater analogy, maybe, is that polling resembles a high-wire act. A presidential election performs out over many months, sometimes to rising consideration and constructing anticipation. Whether pollsters will slip up and fail of their estimates inevitably turns into a little bit of gentle election drama itself.

When forecasts go awry, as they did in 2016, astonishment inevitably follows. For instance, Nate Silver, the information journalist who based the FiveThirtyEight.com polling-analysis and predictions web site, stated Donald Trump’s victory was, broadly speaking, “the most shocking political development of my lifetime.”

Many pollsters insist that election polls are snapshots, not prophesies. But they don’t a lot thoughts crowing when their last surveys come close to estimating the result.

An instance of pollster braggadocio got here a month after the 2016 presidential election, when Rasmussen Reports declared that it had stated all alongside “it was a much closer race than most other pollsters predicted. We weren’t surprised Election Night … look who came in second out of 11 top pollsters who surveyed the four-way race.”

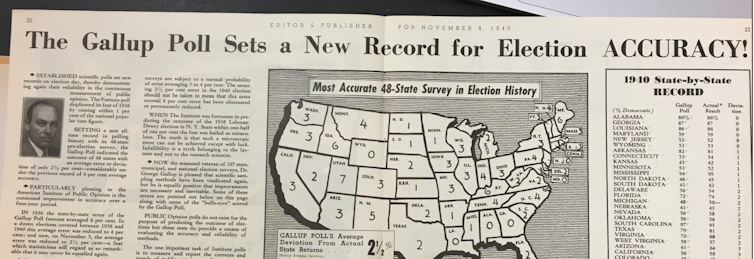

George Gallup did a lot the identical within the early years of recent survey analysis, taking out self-congratultory ads within the Editor & Publisher commerce journal to tout polling successes in presidential races in 1940 and 1944. “The Gallup Poll Sets a New Record for Election Accuracy!” a type of adverts proclaimed.

[Get our most insightful politics and election stories. Sign up for The Conversation’s Politics Weekly.]

Which polls to observe?

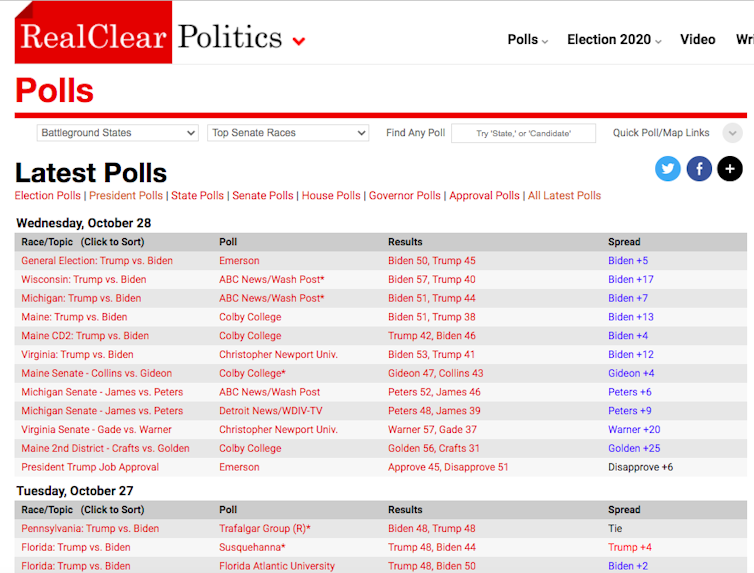

The proliferation of surveys through the years – Nate Silver’s web site offers ratings of dozens of pollsters – additionally permits a form of team-sport method to election polls: Savvy shoppers can determine and observe most well-liked pollsters and principally ignore the remaining. Not that that is essentially advisable, however it’s an possibility allowed by the abundance of polls, lots of which will be routinely tracked within the runup to elections at RealClearPolitics.com.

So, for instance, supporters of Donald Trump might take coronary heart from Rasmussen surveys, which have been far more favorable to the president throughout the 2020 marketing campaign than, say, polls conducted for CNN.

Polling, basically, is an imperfect try at offering perception and clarification. The want for perception and clarification is, after all, by no means ending, so polls endure regardless of their flaws and failures. They absolutely will stay options of American life, regardless of how subsequent week’s election seems.

W. Joseph Campbell, Professor of Communication Studies, American University School of Communication

This article is republished from The Conversation underneath a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.