Mojtaba Sadegh, Boise State University; Ata Akbari Asanjan, NASA, and Mohammad Reza Alizadeh, McGill University

Two wildfires erupted on the outskirts of cities near Los Angeles, forcing greater than 100,000 people to evacuate their houses Monday as highly effective Santa Ana winds swept the flames by means of dry grasses and brush. With robust winds and very low humidity, giant components of California have been below pink flag warnings.

High fire threat days have been frequent this 12 months as the 2020 wildfire season shatters data throughout the West.

More than 4 million acres have burned in California – 4% of the state’s land space and greater than double the earlier annual report. Five of the state’s six largest historical fires happened in 2020. In Colorado, the Pine Gulch fire that began in June broke the record for dimension, solely to be topped in October by the Cameron Peak and East Troublesome fires. Oregon noticed one among the most destructive fire seasons in its recorded history.

What precipitated the 2020 fire season to grow to be so extreme?

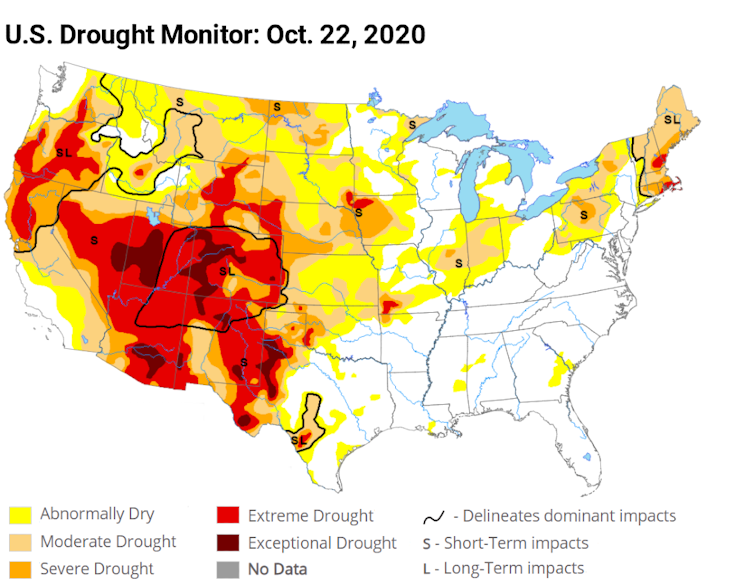

Fires thrive on three components: warmth, dryness and wind. The 2020 season was dry, however the Western U.S. has seen worse droughts in the latest decade. It had a number of record-breaking warmth waves, however the fires didn’t essentially comply with the areas with the highest temperatures.

What 2020 did have was warmth and dryness hitting concurrently. When even a reasonable drought and warmth wave hit a area at the similar time, together with wind to fan the flames, it turns into a strong force that may gas megafires.

That’s what we’ve been seeing in California, Colorado and Oregon this 12 months. Research exhibits it’s occurring extra usually with larger depth, and affecting ever-increasing areas.

Climate change intensified dry-hot extremes

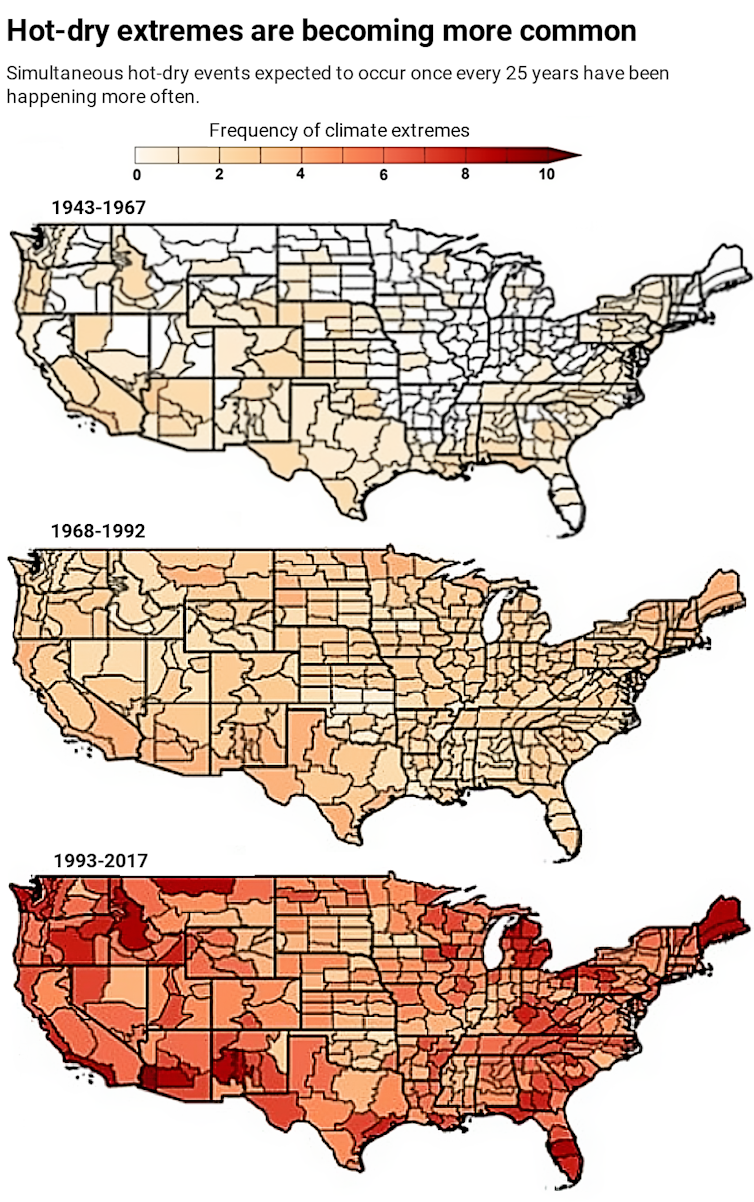

We are scientists and engineers who research local weather extremes, together with wildfires. Our research exhibits that the chance of a drought and warmth wave occurring at the similar time in the U.S. has elevated considerably over the previous century.

The sort of dry and scorching circumstances that might have been anticipated to happen solely as soon as each 25 years on common have occurred 5 to 10 instances in a number of areas of the U.S. over the previous quarter-century. Even extra alarming, we discovered that extreme dry-hot circumstances that might have been anticipated solely as soon as each 75 years have occurred three to six instances in lots of areas over the similar interval.

We additionally discovered that what triggers these simultaneous extremes seems to be altering.

During the Dust Bowl of the Thirties, the lack of rainfall allowed the air to grow to be hotter, and that course of fueled simultaneous dry and scorching circumstances. Today, excess heat is a larger driver of dry-hot circumstances than lack of rain.

This has essential implications for the way forward for dry-hot extremes.

Warmer air can maintain extra moisture, so as global temperatures rise, evaporation can suck extra water from crops and soil, main to drier circumstances. Higher temperatures and drier circumstances imply vegetation is extra flamable. A research in 2016 calculated that the extra warmth from human-caused local weather change was accountable for nearly doubling the quantity of Western U.S. forest that burned between 1979 and 2015.

Worryingly, now we have additionally discovered that these dry-hot wildfire-fueling circumstances can feed on each other and spread downwind.

When soil moisture is low, extra photo voltaic radiation will flip into smart warmth – warmth you possibly can really feel. That warmth evaporates extra water and additional dries the setting. This cycle continues till a large-scale climate sample breaks it. The warmth may also set off the similar suggestions loop in a neighboring area, extending the dry-hot circumstances and elevating the chance of dry-hot extremes throughout broad stretches of the nation.

All of this interprets into larger wildfire threat for the Western U.S.

In Southern California, for instance, we discovered that the variety of dry-hot-windy days has elevated at a higher charge than dry, scorching or windy days individually over the previous 4 a long time, tripling the number of megafire danger days in the area.

2020 wasn’t regular, however what’s regular?

If 2020 has proved something, it’s to count on the surprising.

Before this 12 months, Colorado had not recorded a fire of over 10,000 acres beginning in October. This 12 months, the East Troublesome fire grew from about 20,000 acres to over 100,000 acres in lower than 24 hours on Oct. 21, and it was practically 200,000 acres by the time a snowstorm stopped its advance. Instead of going snowboarding, lots of of Coloradans evacuated their houses and nervously watched whether or not that fire would merge with one other big blaze.

This just isn’t “the new normal” – it’s the new irregular. In a warming local weather, taking a look at what occurred in the previous now not gives a way of what to count on in the future.

“The growth that you see on this fire is unheard of,” Grand County Sheriff Brett Schroetlin said of the East Troublesome fire on Oct. 22. “We plan for the worst. This is the worst of the worst of the worst.”

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

There are different drivers of the rise in fire injury. More individuals transferring into wildland areas means there are extra automobiles and energy traces and different potential ignition sources. Historical efforts to management fires have additionally meant extra undergrowth in areas that might have naturally burned periodically in smaller fires.

The query now’s how to handle this “new abnormal” in the face of a warming local weather.

In the U.S., one in three homes are built in the wildland-urban interface. Development plans, building methods and constructing codes can do extra to account for wildfire dangers, together with avoiding flammable supplies and potential sources of sparks. Importantly, residents and policymakers want to sort out the drawback at its root: That contains chopping the greenhouse fuel emissions which are warming the planet.

Mojtaba Sadegh, Assistant Professor of Civil Engineering, Boise State University; Ata Akbari Asanjan, Research Scientist, Ames Research Center, NASA, and Mohammad Reza Alizadeh, Ph.D. Student, McGill University

This article is republished from The Conversation below a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.