Albert C. Lin, University of California, Davis

On Feb. 28, 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in West Virginia v. EPA, a case that centers on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s authority to regulate greenhouse gas emissions that drive climate change. How the court decides the case could have broad ramifications, not just for climate change but for federal regulation in many areas.

This case stems from actions over the past decade to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from power plants, a centerpiece of U.S. climate change policy. In 2016, the Supreme Court blocked the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan, which was designed to reduce these emissions. The Trump administration repealed the Clean Power Plan and replaced it with the far less stringent Affordable Clean Energy Rule. Various parties challenged that measure, and a federal court invalidated it a day before Trump left office.

The EPA now says that it has no intention to proceed with either of these rules, and plans to issue an entirely new set of regulations. Under such circumstances, courts usually wait for agencies to finalize their position before stepping in. This allows agencies to evaluate the evidence, apply their expertise and exercise their policymaking discretion. It also allows courts to consider a concrete rule with practical consequences.

From my work as an environmental law scholar, the Supreme Court’s decision to hear this case is surprising, since it addresses regulations the Biden administration doesn’t plan to implement. It reflects a keen interest on the part of the court’s conservative majority in the government’s power to regulate – an issue with impacts that extend far beyond air pollution. https://www.youtube.com/embed/tFHDE52B1qU?wmode=transparent&start=0 On Oct. 14, 2020, then-Sen. Kamala Harris questions Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett about her views on climate change.

How much latitude does the EPA have?

The court granted petitions from coal companies and Republican-led states to consider four issues. First, under Section 111 of the Clean Air Act, can the EPA control pollution only by considering direct changes to a polluting facility? Or can it also employ “beyond the fenceline” approaches that involve broader policies?

Section 111 directs the EPA to identify and regulate categories of air pollution sources, such as oil refineries and power plants. The agency must determine the “best system of emission reduction” for each category and issue guidelines quantifying the reductions that are achievable under this system. States then submit plans to cut emissions, either by adopting the best system identified by the EPA or choosing alternative ways to achieve equivalent reductions.

In determining how to cut emissions, the Trump administration considered only changes that could be made directly to coal-fired power plants. The Obama administration, in contrast, also considered replacing those plants with electricity from lower-carbon sources, such as natural gas and renewable fuels.

The question of EPA’s latitude under Section 111 implicates a landmark decision of administrative law, Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council. That 1984 ruling instructs courts to follow a two-step procedure when reviewing an agency’s interpretation of a statute.

If Congress has given clear direction on the question at issue, courts and agencies must follow Congress’ expressed intent. However, if the statute is “silent or ambiguous with respect to the specific issue,” then courts should defer to the agency’s interpretation of the statute as long as it is reasonable.

In recent years, conservative Supreme Court justices have criticized the Chevron decision as too deferential to federal agencies. This approach, they suggest, allows unelected regulators to exercise too much power.

Could this case enable the court’s conservatives to curb agencies’ authority by eliminating Chevron deference? Perhaps not. This case presents a less-than-ideal vehicle for revisiting Chevron’s second step.

The Trump EPA argued that the “beyond the fenceline” issue should be resolved under the first step of Chevron. Section 111, the administration contended, flatly forbids the EPA from considering shifting to natural gas or renewable power sources. The lower court accordingly resolved the case under Chevron’s first step – rejecting the Trump EPA argument – and did not decide whether EPA’s view merited deference under Chevron’s second step.

Chevron deference aside, a restrictive interpretation of Section 111 could have serious implications for EPA’s regulatory authority. A narrow reading of Section 111 could rule out important and proven regulatory tools for reducing carbon pollution, including emissions trading and shifting to cleaner fuels.

Do climate change regulations infringe on state authority?

The second question focuses on Section 111’s allocation of authority between the states and the federal government. The Clean Air Act requires the EPA to issue emission reduction guidelines that states must follow in establishing pollution standards.

In repealing the Clean Power Plan, the Trump administration argued that the plan coerced states to apply EPA’s standards, violating the federal-state balance reflected in Section 111. Republican-led states are now making this same argument.

However, the matter before the court is the Trump administration’s Affordable Clean Energy Rule, which does not present the same federalism issue. The question of whether the now-abandoned Clean Power Plan left the states sufficient flexibility is moot.

In my view, the court’s willingness to nonetheless consider federalism aspects of Section 111 could bode poorly for the EPA’s ability to issue meaningful emission reduction guidelines in the future.

Is carbon pollution from power plants a ‘major question’?

The third issue that the court will consider is whether regulation of power plant carbon emissions constitutes a “major question.” The major questions doctrine provides that an agency may not regulate without clear direction from Congress on issues that have vast economic or political impacts.

The Supreme Court has never defined a major question, and it has applied the doctrine on only five occasions. In the most prominent instance, in 2000, it invalidated the Food and Drug Administration’s attempt to regulate tobacco. The court noted that the agency had never regulated tobacco before, its statutory authority over tobacco was unclear, and Congress had consistently assumed that the FDA lacked such authority.

By comparison, the Supreme Court has affirmed and reaffirmed the EPA’s authority to regulate greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act, and the agency’s authority to regulate power plant pollution under Section 111 is not in doubt.

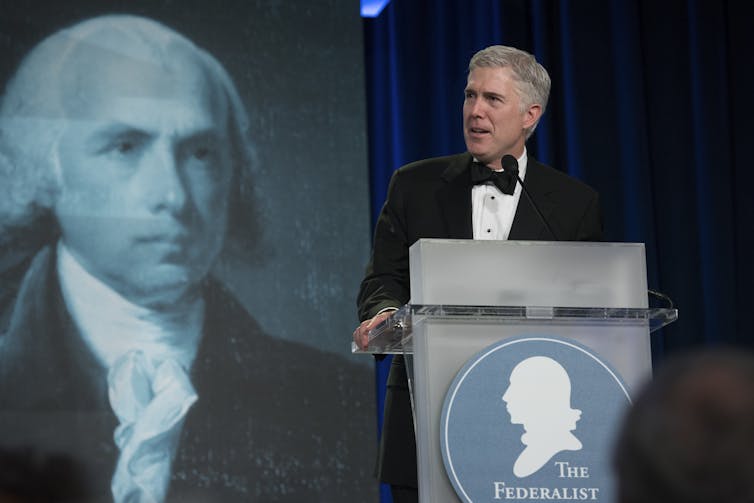

However, when the Supreme Court struck down the workplace COVID-19 vaccine-or-test mandate on Jan. 13, 2022, Justice Neil Gorsuch penned a concurrence touting the major questions doctrine’s potential to check the power of federal agencies. An expansive interpretation of the major questions doctrine here could cripple EPA’s ability to respond to climate change under the Clean Air Act.

If the court demands more specific statutory authorization, Congress may not be up to the task. Indeed, many observers fear a broad interpretation of the doctrine might have repercussions far beyond climate change, radically curbing federal agencies’ power to protect human health and the environment, in response to both new threats such as the COVID-19 pandemic and familiar problems such as food safety.

Has Congress delegated too much power to the EPA?

Finally, the court will consider whether Section 111 delegates too much lawmaking authority to EPA – a further opportunity for conservative justices to curb the power of federal agencies. The nondelegation doctrine bars Congress from delegating its core lawmaking powers to regulatory agencies. When Congress authorizes agencies to regulate, it must give them an “intelligible principle” to guide their rulemaking discretion.

For decades, the court has reviewed statutory delegations of power deferentially. In fact, it has not invalidated a statute for violating the nondelegation doctrine since the 1930s.

In my view, Section 111 should easily satisfy the “intelligible principle” test. The statute sets out specific factors for the EPA to consider in determining the best system of emission reduction: costs, health and environmental impacts, and energy requirements.

Still, the case presents an opportunity for the court’s conservatives to invigorate the nondelegation doctrine. A 2019 dissenting opinion by Justice Gorsuch, joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Clarence Thomas, advocated a more stringent approach in which agencies would be limited to making necessary factual findings and “filling up the details” in a federal statutory scheme. Whether Section 111 – or many other federal laws – would survive this approach is unclear.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter.]

Albert C. Lin, Professor of Law, University of California, Davis

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.